Since moving to the Sunnyside neighborhood in northwest Denver six years ago, I’ve always been struck by all of the different types of houses. There are stately Victorians, Denver squares, modern builds, large apartment complexes, and lots of small ranches, similar to ours. At first, the distribution of the housing styles seems random, but if you look a little closer, it quickly becomes clear how distinct building and settlement patterns have developed over time in Denver’s neighborhoods, due to economic and social forces that run deep through its history.

Our cities and neighborhoods have been segregated across racial lines for centuries. According to an analysis of the 2010 Census, the Denver-Aurora metro area is in the middle of the pack among major metro areas in terms of current racial segregation. But a quick look at this visual representation of racial demographics across the country, shows that—middle of the pack or not—racial segregation runs rampant across most parts of Colorado, including Denver.

Where you live matters for your health. A lot. It is well established that zip code is a better predictor of health than a person’s genetic code. The conditions of a person’s house, its cost, and aspects of their neighborhood—including walkability, open space accessibility, crime, and even the prevalence of racial segregation—impact a person’s ability to stay healthy. Owning a home is also a gateway to economic security and long-term well-being and accounts for much of the significant racial wealth gap that persists in our country.

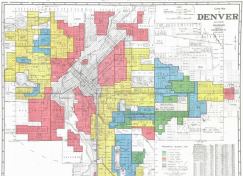

So what does racial segregation have to do with the housing stock in my neighborhood? Due to our country’s tortured history of institutional racism, the two are pretty much inseparable. For most of our country’s history, countless laws and policies ensured living in a high-quality house in a good neighborhood, and the associated health benefits, was only a reality for white Americans. Redlining was a decades-long Federal Housing Administration practice of only insuring mortgage loans in predominantly white neighborhoods. This reinforced racial segregation and led to substandard housing in non-white neighborhoods across the country. Many times when walking down my block, I’ve wondered why the houses on the east side of the block, including ours, were smaller than and not as nice as those literally across the street. It turns out our street, Bryant Street, was the actual boundary for the “redlined” zone where we live in northwest Denver.

Decades later, the disparities in access to quality housing and neighborhoods that those policies and practices helped shape persist—in my neighborhood and neighborhoods all over the state. At CCMU, we recently launched a project called Waiting for Health Equity, which explores the root causes of health disparities, like discriminatory housing policies, through a graphic novel. Chapter 2 is out today. Our board and staff have also recently publicly committed to deepening our understanding and leadership around health equity, so we are accountable to unpacking our own internal policies and implicit biases that perpetuate disparities and working with other organizations to do the same. We hope you’ll join us.